Fiona Conrads (1950), the Netherlands, 28 April, 1969

“Those first nights we slept on chairs in the auditorium. The mayor came to check on us and did not like it one bit that girls were sleeping there as well. We just said: ‘Hi, we are not going to leave anytime soon!’

“I was one of the few female students there. My parents had wanted me to finish nursing school, but I was determined to go to university. At seventeen I ran away from home and started to live in a commune.

“I think that people will begin to protest when the gap between their possible future and the reality in which they live becomes too large. In the late sixties, the Dutch economy flourished and consequently there was a need for many highly educated people. Young people from working class families were recruited to study on scholarships. ‘Good, now it’s our turn!’ those boys and girls thought. But they clashed with the existing traditions. For example, there were fraternities you were only allowed to join if your father’s bank account was fat enough.

“I really hated the fifties and early sixties. You were not in charge of your own life. We saw what the elite did wrong. We were against the war in Vietnam, we idolised Martin Luther King. We were very concerned with what was good and bad – the process of coming to terms with World War II had only just started. We participated in protests and organised debates and expositions.

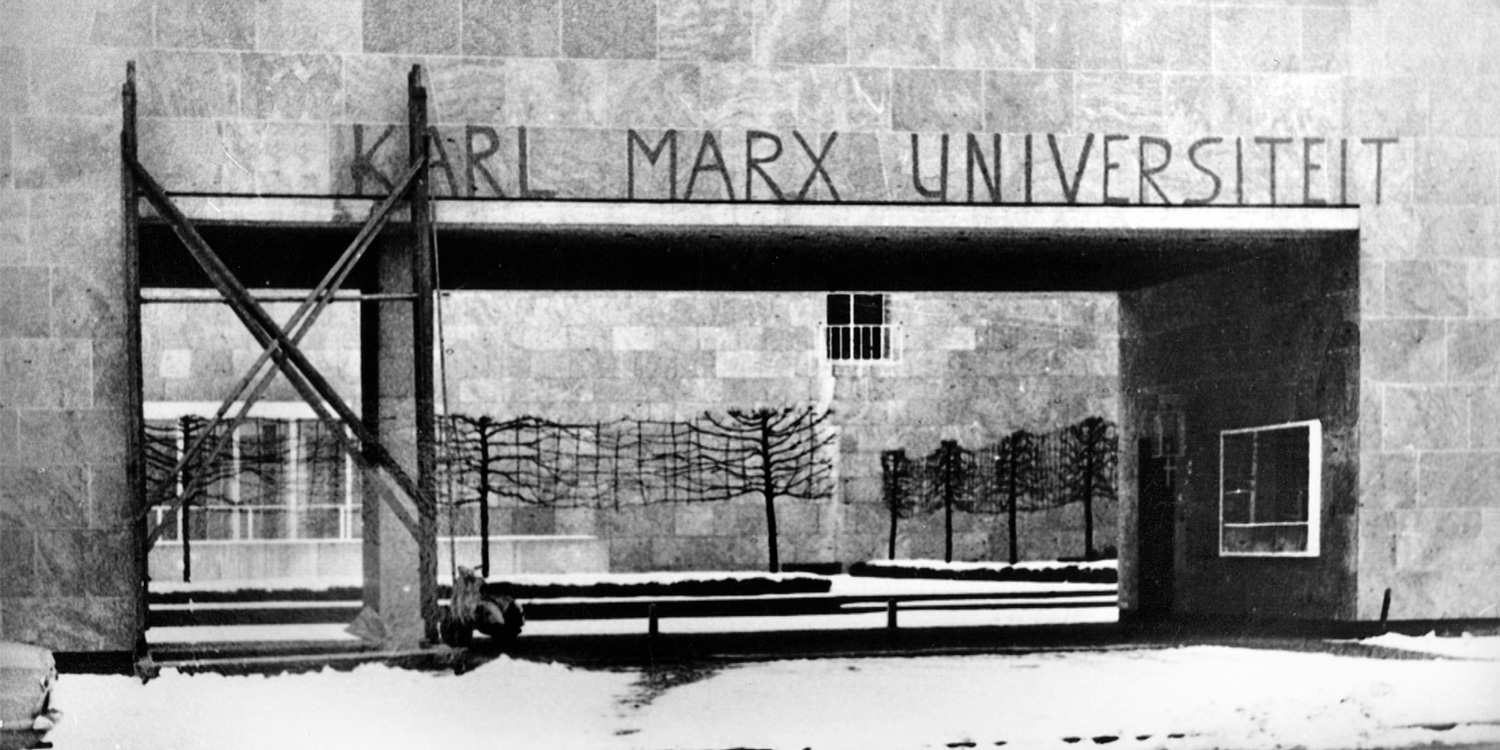

“In 1969, the universities were going through a turbulent period. Sit-ins were held and a few young men painted the words ‘Karl Marx University’ above the main entrance. The occupation of the telephone exchange was the last straw for the chancellor of the university. He decided to suspend all classes. That is when we occupied the college. It was unthinkable not to participate; you were a member of a club, it was part of your identity.

“In retrospect, that was exactly why what we were doing was so dangerous: your personal life, your living arrangements, your friendships, your education – everything was connected. When the club fell apart, I lost everything at once. In the period that followed the university occupation, the Communist Unity Movement of the Netherlands emerged. They had a very strict doctrine. That discipline again; I would have none of it. I was certainly impressed by the ‘young Marx’, but I did not believe in Marxism-Leninism. Conflicts arose in our small group; in the end, there were only six of us left. Yes, I’m still disillusioned with it.”

Occupation of the Catholic College in Tilburg

On 28 April 1969, the then Catholic College in Tilburg, a city in the south of the Netherlands, was occupied by students. Inspired by the student protests in Paris of 1968, the Dutch students demanded changes to the educational system and more participation and democracy. Eight days after the students had occupied the buildings, most of their demands were met. Later that month, students occupied the University of Amsterdam. In 1971, the Law on University Governance Reform was passed by which the student participation was officially arranged. (Incidentally, that influence was curtailed in the nineties. In 2015, a few hundred students occupied the University of Amsterdam again. Their protest signs read: ‘More participation, more democracy!’