Estera Knaap-Giurgi was nineteen – ‘still a child’ – when she witnessed the execution of the dictator couple Ceaușescu, broadcast live on her neighbours’ TV. She lived in the tiny village of Poienile Izei, near the Ukrainian border, where the villagers had followed the violent revolution that had preceded the execution from a safe distance, gathered in front of the few televisions the small community owned. A strange feeling of pity washed over Knaap when she saw the Ceaușescus collapse before the firing squad. But a sense of relief predominated: the dictator was eliminated once and for all.

A new era began for Romania, and Knaap soon met a boy from the Netherlands who was helping with relief transports that had started after the revolution. They fell in love, and Knaap followed him to the Netherlands, while the revolution all but disappeared from her memory. Making a phone call to Romania was difficult at the time, and so was getting a travel visa for the Netherlands. She did not consider taking part in the rebuilding of her country. Knaap: “You know, my generation grew up with slogans such as ‘work, don’t think!’. We shouted it during marches together with the factory workers. I had no idea what democracy was or a political party, let alone a multi-party system.”

Early 2017, Knaap walked in a protest in The Hague. Social media had brought Romania a lot closer. In January and February, hundreds of thousands of Romanians took to the streets to protest a decree that would actually make corruption in their country legal. These demonstrations were the largest since the revolution. A solidarity campaign was organised in The Hague, in which Knaap participated. By then Knaap was working at a property development company, and she had almost graduated from the Photo Academy (‘a hobby that got a bit out of hand’). Knaap: “During that demonstration, police officers protected us. They closed off certain streets for us, for example. For free! That might sound quite ordinary to someone from the Netherlands, but for me, that is still something special. They could also have said ‘sod off to your own country'. "

Knaap has never been able to shake off her deeply rooted distrust of uniforms. As a young girl, she saw how the Securitate, Ceauşescu’s secret police, searched their home. Her father illegally copied Christian texts on his forbidden typewriter. He had to report to the Securitate, and although they never held him long, Knaap remembers well how she thought she might never see him again.

During the demonstration in The Hague, the past suddenly emerged. How must those people who fought during the revolution have felt? Instead of being protected by the police or the army, they were shot at. In Timișoara alone, where the uprising started, more than one hundred people were killed. Knaap: “I was ashamed that I knew so little about it.” She decided to go to Timişoara with her camera to speak with victims and surviving relatives and to take their pictures. “Sometimes, after a conversation, I would walk through the city all afternoon, crying. Talking about it now makes me well up again.”

The photographs and stories are brought together in the book Timișoara, December 1989. Ideally, she would also publish the book in Romania, but that is the one place where it is difficult to sell the story: “After the revolution, it was pretty easy to get your hands on a ‘certificate of participation in the revolution’. Having two witnesses who said you were there was enough to become eligible for compensation. That is why many Romanians do not trust the stories of victims of the revolution.”

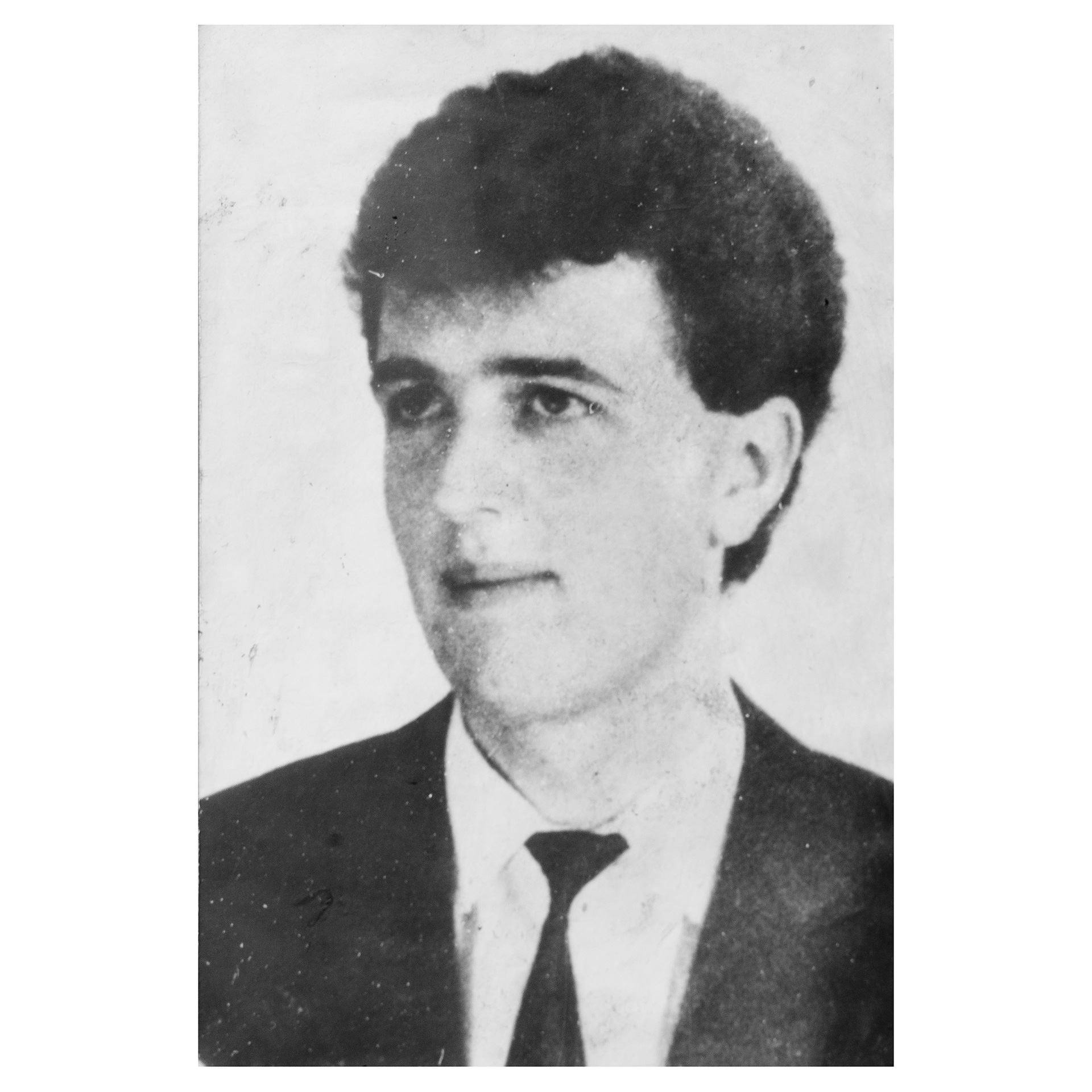

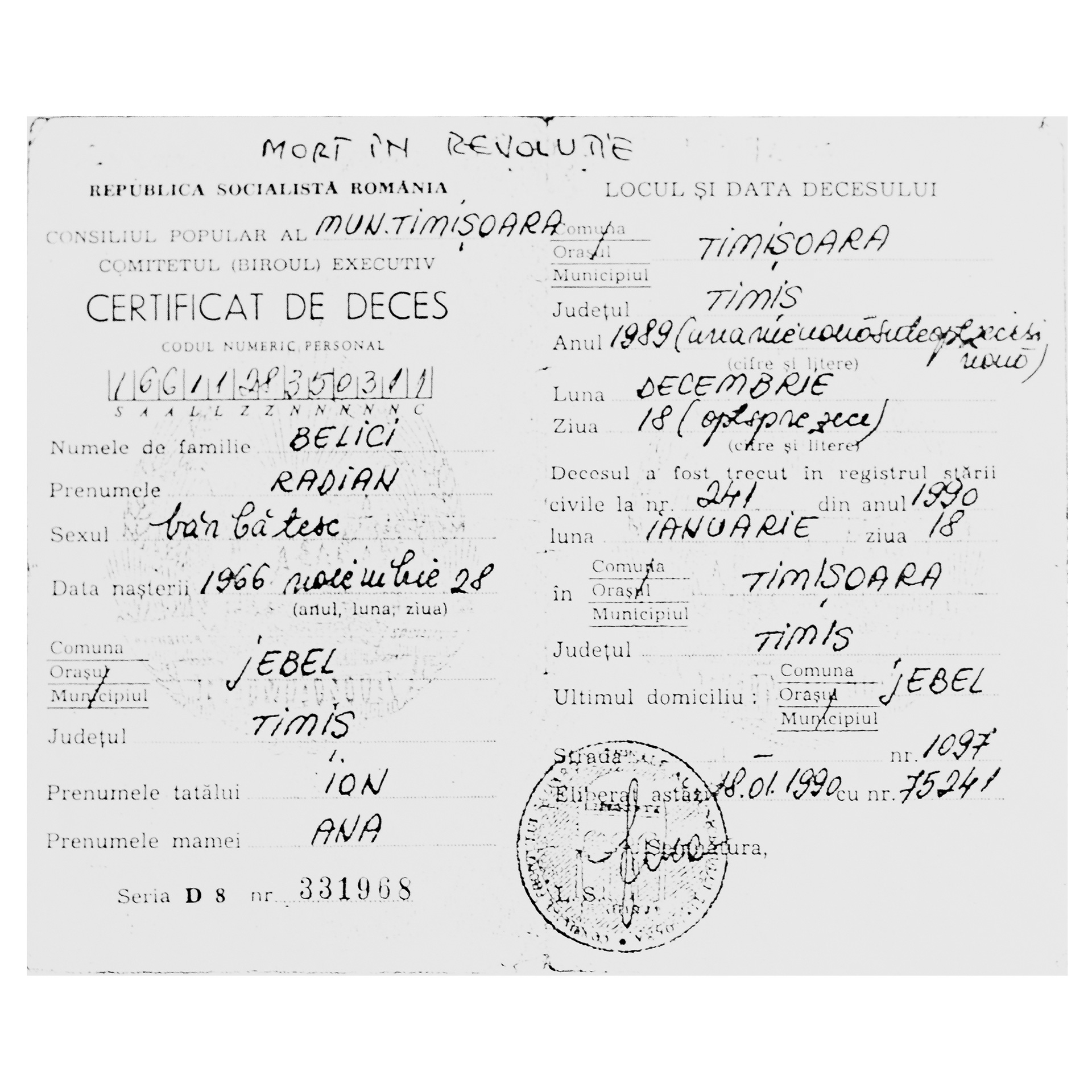

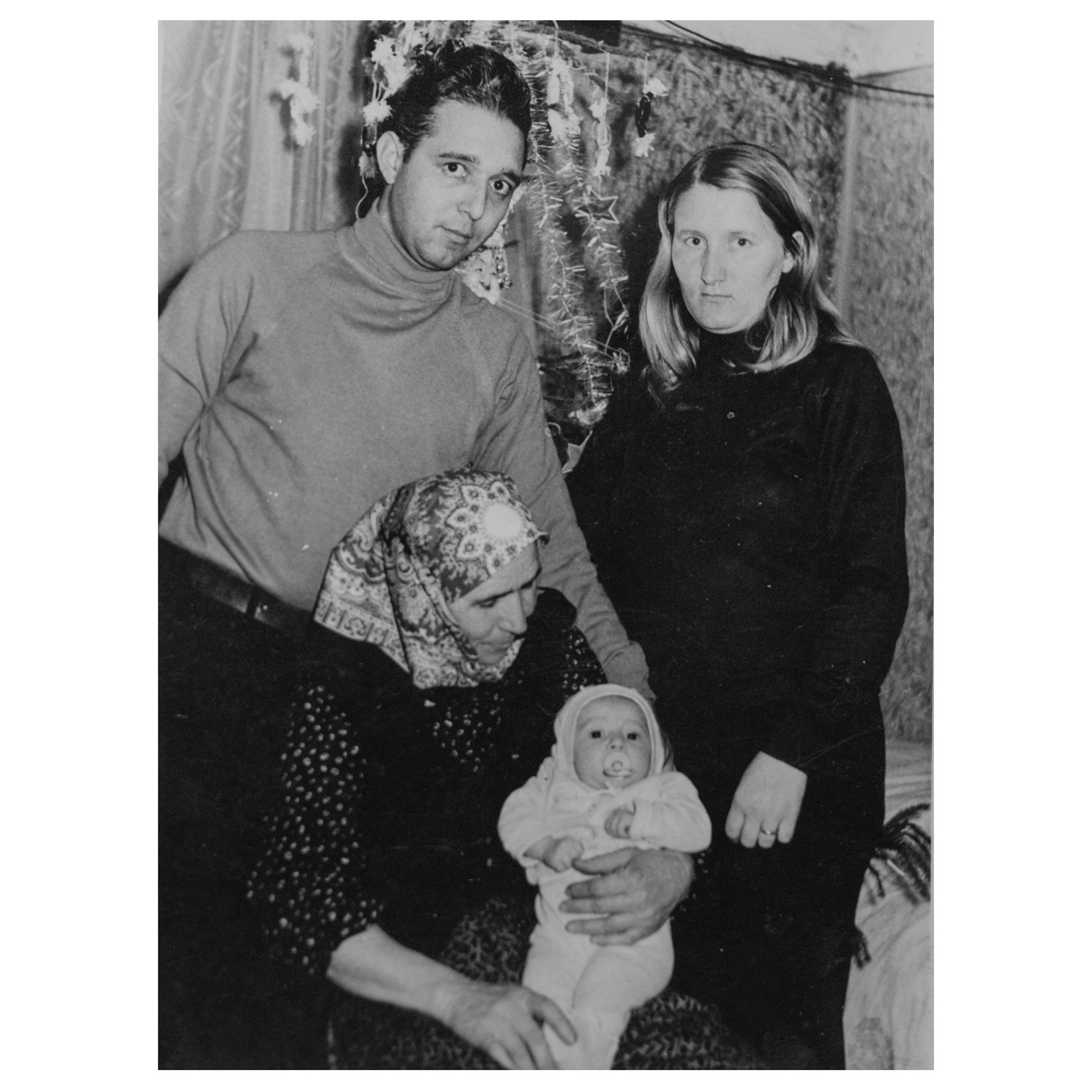

“Ana and Ion Belici lived in Jebel, a village near Timișoara. On 17 December 1989, their son Radian who was then 23 joined the protesters in Timișoara, together with his wife and daughter. There was a sinister atmosphere. Radian sent his wife and daughter back, promising to follow them soon. But he never arrived home. He was mortally wounded by a bullet, and his body was brought to the mortuary of the regional hospital. His parents and his wife were not allowed to see him; the military-guarded hospital was hermetically sealed from the outside world. Not until 22 December could they go in. But by then, Radian’s body had been stolen from the mortuary, brought to Bucharest, and cremated – just like the bodies of 42 others. Mrs Belici cries when she explains how – when she visited the location of the sewer pipe for the first time – she took a handful of earth, hoping it would contain some of her son’s ashes. After the revolution, she visited Piata 700 in Timișoara, the place where her son was shot, on a daily basis. Now she can no longer go as often because of her age and poor health, but she still manages to do it at least once a week.”

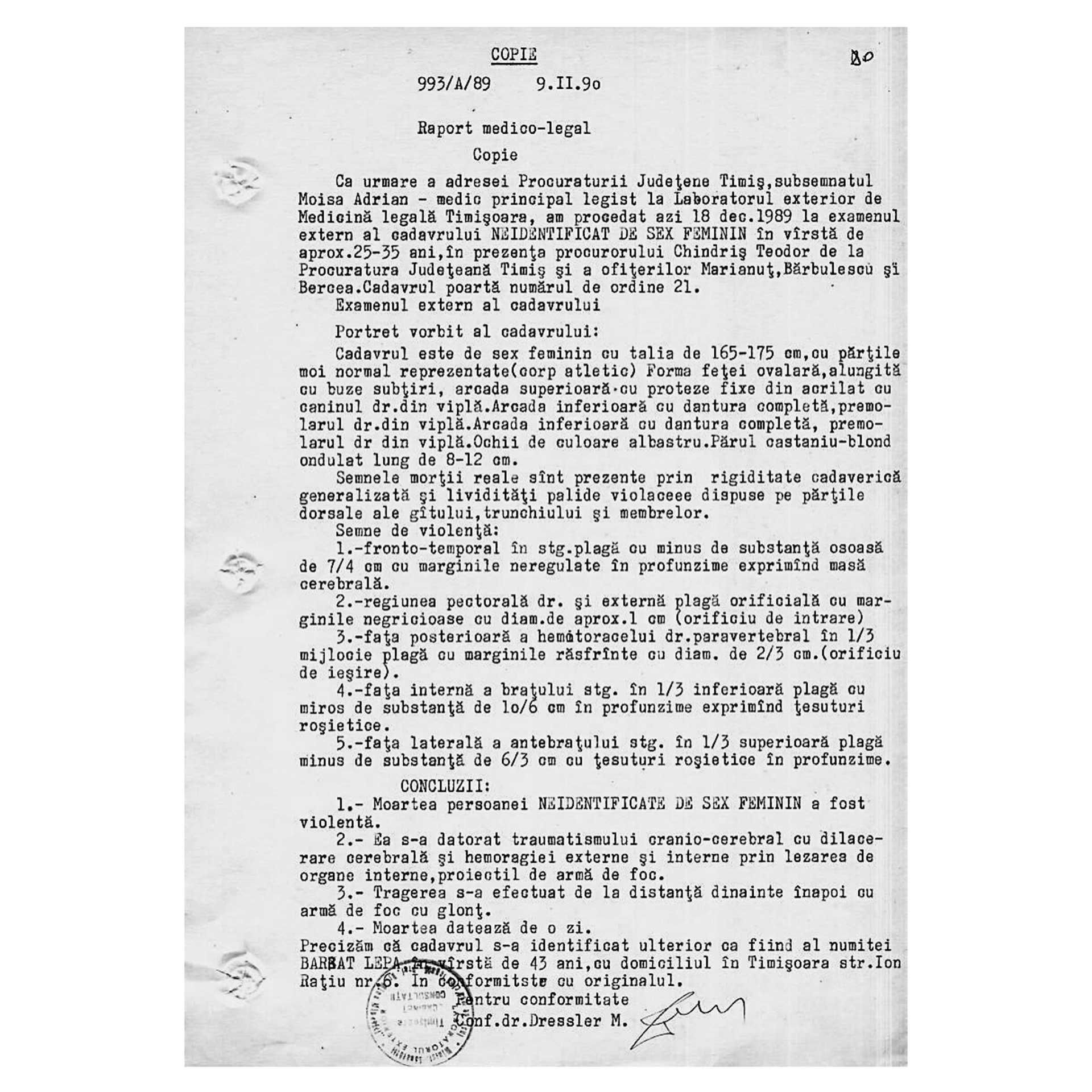

“Ioana Barbat had just turned 12 when she visited the centre of Timișoara with her father and mother on 17 December. Her mother wanted to see with her own eyes what was going on in the city. They had barely arrived in the centre when a soldier with a machine gun started shooting at them. Ioana’s mother was hit in the head and died instantly. Her father was severely wounded. Iona herself miraculously managed to get away with only a small injury.

Her father was cared for in the local hospital. However, the following day Ioana found out that her mother’s body had disappeared from the mortuary. Those responsible for her death were never convicted.”

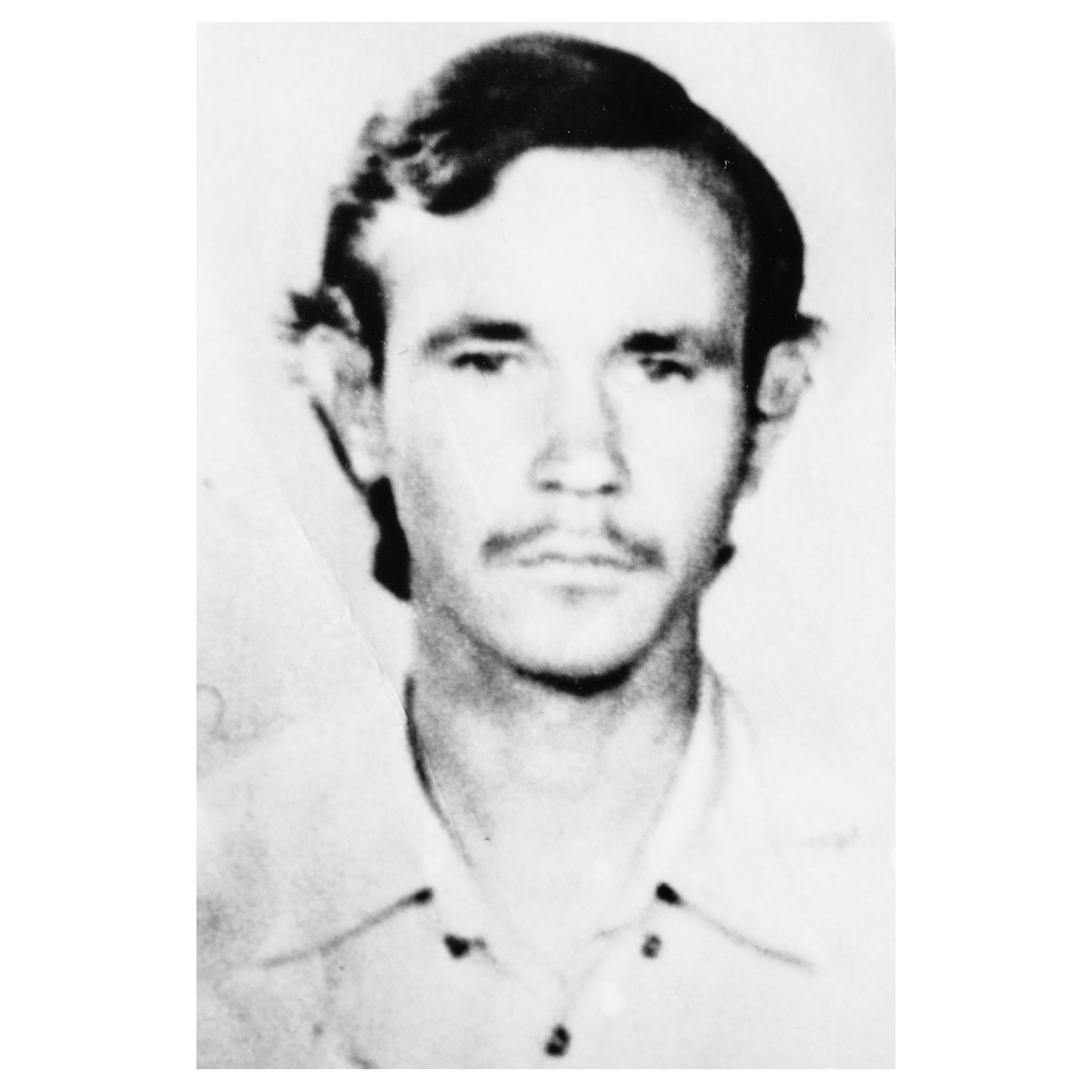

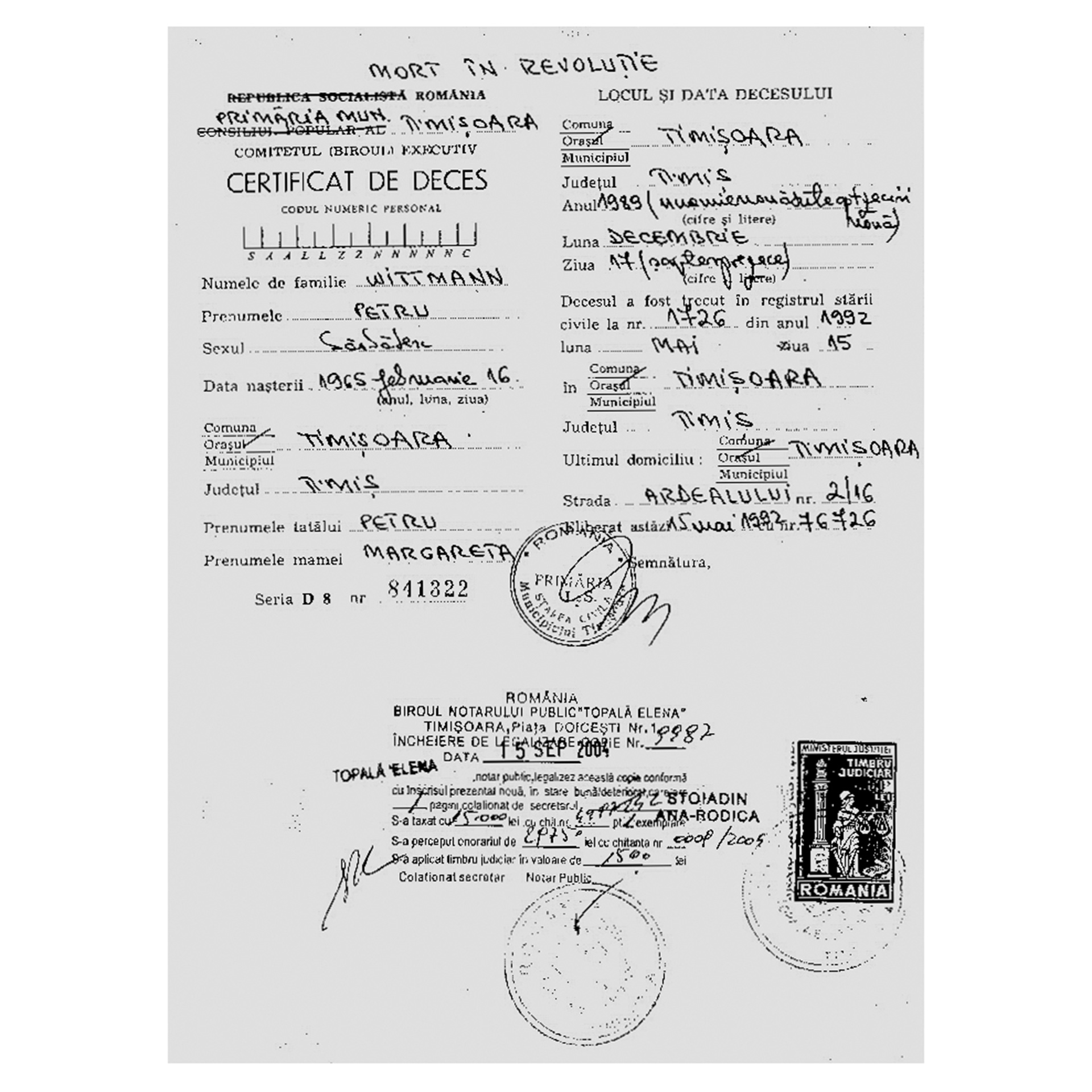

“For a long time, it remained unclear what exactly had happened with Ericha Wittman’s brother, Petru, in December 1989. He had gone out by himself, and nobody had raised the alarm when he was shot dead on the steps of the Orthodox Cathedral. The next day, his body had gone without leaving a trace. Repeated requests from his family members to the authorities were invariably answered with: ‘He probably fled the country.’ Only two and a half years later, on 15 May 1992, did his family receive the official death certificate.”