Karol Radziszewski worries about the position of gay people in Poland. “A lot of older gay men considered Poland to be a safer environment for them during the communist era than in the current day,” he says in fluent English via Skype. The artist is the founder and publisher of DIK Fagazine, an artistic gay magazine on the former Eastern bloc, in which arty pictures of (semi-)naked men are alternated with in-depth interviews and features. In 2015, Radziszewski also founded The Queer Archives Institute, an archive for queer history in Eastern Europe. Since then, he has organized expositions on this subject around the world.

Forgotten History

Poland de-criminalized homosexuality in 1932, decades before many other European countries did. It gave the gay community a certain measure of freedom. It wasn’t so much that homosexuality was accepted as it was ignored. People simply pretended it didn’t exist. “A lot of gay men were married, but had sex with men on the side,” Radziszewski explains. “Homophobia came mostly from the church.”

Lukasz Sculz did research into homosexual media in communist Poland at the University of Antwerp. He thinks that when it comes to gay rights, Poland’s communist days should not be romanticized. “In the 1980s, gay men were often robbed, beaten and even killed in cruise areas by groups of straight men. Moreover, they were faced with all kinds of obstacles. For instance, they were discriminated against in housing.”

“Even the term coming out was used.”

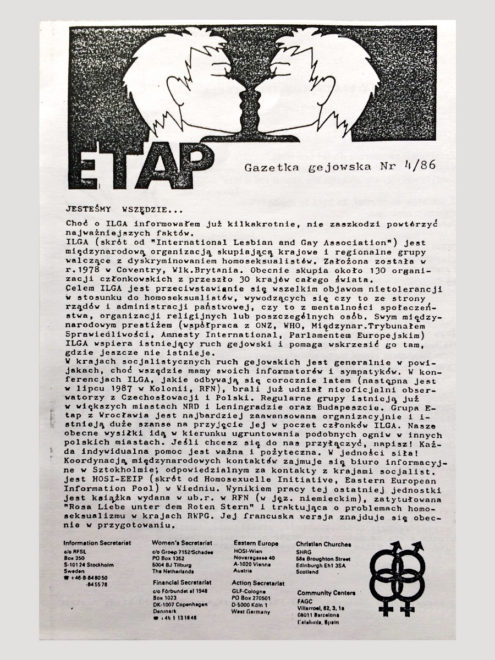

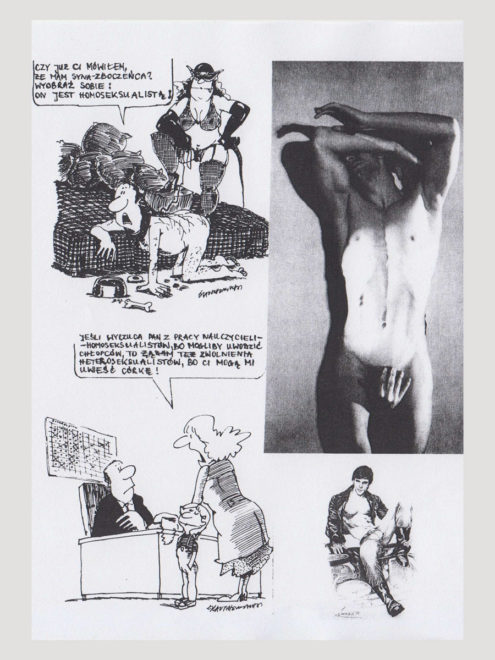

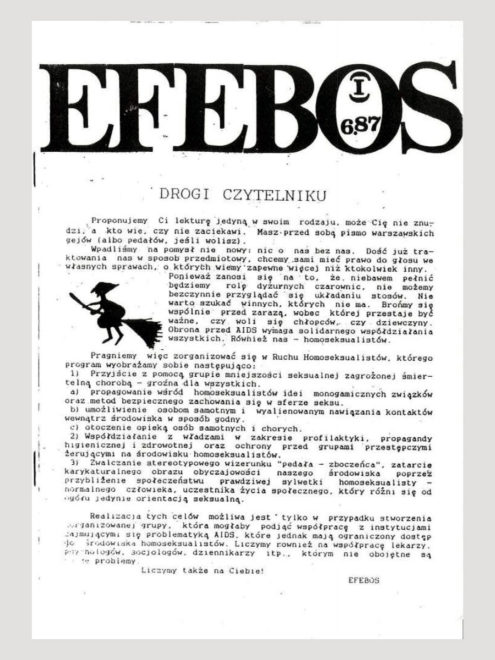

As an academic specialized in media, Szulc dove into the history of the first Polish gay magazines. “When I found the magazines, I was in shock. This history had completely been forgotten,” Szulc says about the simple magazines called Filo and Biuletyn, which was founded in 1983 and later renamed ‘Etap’, Polish for phase. Just like today, the influence of the western world on gay consciousness in Poland was big back then. “Filo used to translate and print entire articles from smuggled gay rags from France, Germany or England. It was only later that the editors wrote their own stories,” according to Sculz. The long articles of Filo and Etap were alternated here and there with erotic drawings of male nudes.

Szulc was surprised at the knowledge that the isolated communist country had of western life. “In Filo, homosexuality was sometimes denoted with the English word gay, rather than the Polish homoseksualista.” When it came to the content of the magazines, the western influence could also clearly be seen: “The emphasis was on the visibility of gay people, there were calls to ‘fight for you rights’. Even the term coming out was used.”

Operation Hyacinth

In 1985, Polish gay people were first confronted with outright hostile policies from the authorities. Gay men were registered in a database, supposedly to prevent the spread of HIV. In reality, the men were blackmailed and forced to cooperate with the regime.

The unintended consequence of Operation Hyacinth, as the policy was called, was that it gave gay people in Poland more self-awareness. “’Hyacinth can be considered the Polish ‘Stonewall’’, Radziszewski says, referring to the police raid on a New York gay bar in 1969, an incident that is seen as a catalyst for the birth of the modern American gay rights movement. “There may not have been a brawl or demonstrations, like in New York, but Operation Hyacinth compelled the gay community to reflect on itself and get organized for the very first time. The founding of the first gay rights organization of Poland, the Warsaw Gay Movement, was a direct response to Operation Hyacinth.

The history of the gay rights movement in communist Poland is all the more relevant, now that the very conservative Law and Justice Party is in power, Szulc thinks “We could learn so much from our own history. The current public debate about gay emancipation looks a lot like the debates that we find in the gay magazines of the 80s. Szulc says it’s a pity that Poland doesn’t look toward its own history when fighting homophobia at home, but looks instead, to the American or western past.

THE EUROPEAN UNION AS A PROGRESSIVE BOGEYMAN

The current leader of Law and Justice once defended a ban on ‘gay propaganda’ in schools and stated that homosexuals should not be teachers. Poland is still one of the few countries in the European Union that have a constitutional ban on same-sex marriage. It also doesn’t offer a registered partnership to gay couples.

But we shouldn’t have to expect any better from less conservative politicians when it comes to LGBT rights, says Matheusz Sulwinski. He is the spokesman of Stonewall Grupa, a gay rights group founded in 2015 to counter the Poland of right-wing conservatives. “As long as Law and Justice is in power, we shouldn’t have to expect positive change,” Sulwinski says. “But in the eight years that the liberals were in charge, nothing really happened either. Politicians have never been our allies.” Radziszewski seconds that: “The liberals have done little for the rights of LGBT’s in the past. The left is divided; there are old socialists, young communists and liberals. Young gay people don’t know who to turn to for support.

Researcher Szulc: “After the fall if the Iron Curtain, Poland wanted to be like the west, in a political and economic sense. The country became democratic and capitalist. But more conservative Poles wondered aloud: what will be left of our own identity? The answer turned out to be: our cultural identity, the sense that ‘we are Christians with traditional values”’. Homosexuality became a political issue in the new, democratic Poland. In 2003, when the referendum on accession to the European Union was held, a lot of people raised the specter of Poland being forced to legalize same-sex marriage if it were to become a member state. After all, a law to protect sexual minorities from workplace discrimination was adopted under pressure from the EU. In debates about sexuality and gender, the EU is often cast in the role of the big progressive bogeyman.

“The Law and Justice Party is just looking to see how far it can go.”

Radziszewski says that under this right-wing government, voices of homophobia have been emboldened. “Right-wing politicians have always been anti-gay, but they used to distance themselves from the radical right-wing voices; they were ashamed. Now they support even the most extreme elements of society. That is the worst they have done, I think. This government is looking to see how far it can go.” According to the artist, the government has fostered a climate, in which anti-gay sentiments can flourish. “A gay friend of mine was recently beaten up in the street. There are no hate crime laws in Poland against homophobic violence.”

As a result of this situation, a new generation of gay rights activists is emerging, according. And just like the Polish gays did in the 1980s, the younger generation is looking to the west for its inspiration. Sulwinski, the spokesman of Stonewall Grupa: “The younger generation has little historical knowledge. Especially the youngest generation has never known a time when homosexuality was really taboo.” Radziszewski laments the lack of historical knowledge: “You could tell the young generation of LGBT’s that they used to shoot gay people, they wouldn’t care.” Still, gay people will never become invisible like they were during communism. “That’s what’s changed. We are visible now; even the expressions of homophobia are a testament to that.”