Heidi Krieger is eleven when she discovers a fun pastime: athletics. Things like that don’t go unnoticed in 70s East Germany. A selection and training system refined to perfection monitors school children to determine who’s good at what sport. Shot-put and discus throw were the two little Heidi might be famous for one day.

Heidi knows the deal: being successful in sports equals being successful in life. And so she practices and practices until at fourteen she’s admitted to the Kinder- und Jugendsportschule (sports school for children) of powerful sports club SC Dynamo Berlin, which is funded by the Stasi. Apart from standard subjects like math and languages, she practices weightlifting, discus throw, and shot-put every day. It’s tough, but her coach provides vitamins to build her up. Blue tablets wrapped in tinfoil and packed in plastic.

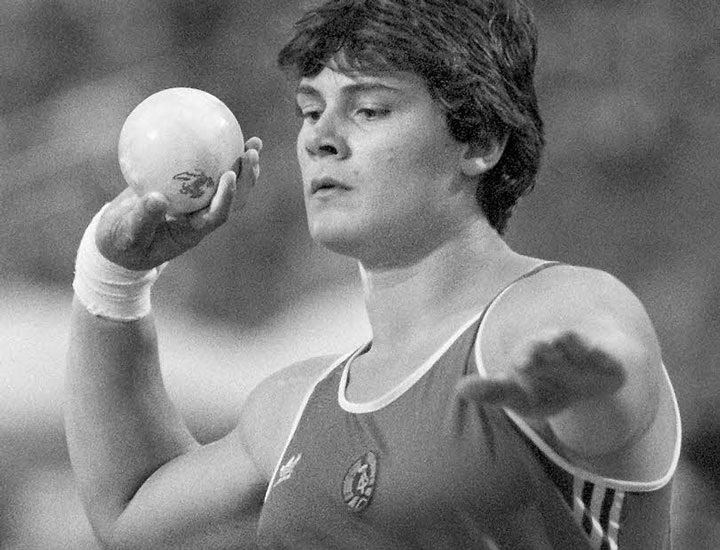

In 1986, when she’s 21, Heidi wins the gold medal for shot-put at the European Olympic Games in Stuttgart. She throws the shot 21.10 meters. Heidi is a success.

But Heidi has been gone for a long time now, and her record was removed from the Olympic list in 2012. The blue pills weren’t vitamins, but the now notorious Oral Turinabol: male sex steroids. Every tablet contained five milligrams of testosterone, and Heidi had taken them daily since she was sixteen, sometimes five a day. We now know her testosterone levels were 37 times that of an average woman at the time. After years of depression, uncertainty, and suicidal tendencies, she decided to have a sex change in 1997. Heidi is now Andreas.

Andres is among the most famous victims of the GDR doping practices. He has a long list of washed out companions who were once celebrated champions like Heidi. Today, they suffer from liver failure and kidney problems, and many have crooked bones and joints. Former female athletes have beards and a deep voice, and some saw their clitoris grow into a small penis. Depression, bulimia, and suicide are common, as are miscarriages and infertility. Some former athletes had children with partial paralysis, clump feet, or Down Syndrome. Others died before they even had children.

That’s the GDR, but the other side of the Iron Curtain has similar stories. West Germany was home to another, iconic victim: heptathlon athlete Birgit Dressel. She passed away in a hospital in Mainz in 1987, when she was 26. Screaming in agony, as the story goes. Dressel was on her way to the top when one day during shot-put practice suddenly her hips started hurting. She died three days later. They found 101 different preparations in her system, ranging from vitamins to illegal muscle enhancers. Her joints were inflamed, her bones crooked. ‘A victim of the pharmaceutical industry,’ according to her father. ‘A tragic coincidence,’ said her sports doctor Armin Klümper, also known as ‘the wonder doctor of Freiburg’.

GDR: A CLASSIFIED PLAN

The GDR called it Staatsplanthema 14.25, a classified plan from 1974 that stated doping was part of the athlete’s training process in the GDR. Some 15,000 East German athletes, both adults and minors, were put on a systematic ‘vitamin’ diet by their coaches. The distribution of colored pills had been prevalent before 1974, but as doping control abroad was improving rapidly, the GDR wanted to be on top of things. To that end, doping was government-controlled from then on.

The GDR doping policy was exposed in 1991 by Brigitte Berendonk in her controversial book Doping Dokumente. Berendonk, herself a former GDR tetrathlon youth champion and West German discus throw (1971) and shot-put (1973) champion, and her biologist husband Werner Franke managed to get their hands on several meticulously described doping plans.

It was especially the sheer scale and systematics revealed by Berendonk that shocked home and abroad. Still, the facts – however minutely documented – are widely denied by politicians, coaches, sports doctors, and athletes. Only in 1998 a number of doctors and politicians involved receives suspended sentences and fines, and a group of victims is offered a – symbolic – compensation. Despite this recognition, people like Berendonk who address doping practices are taunted and even threatened to this day.

WEST GERMANY WAS JUST AS BAD

West Germany, too, had its doping policy – although it didn’t have an official name, and there weren’t any specific plans. And West Germany, too, collectively denied it – although here the denial lasted much longer: until August 2013. It was then Humboldt Universität Berlin published research that ended the long-cherished illusion that only the east was guilty of structural doping abuse. The study revealed that doping use was structural and widespread in the former FRG between 1970 and 1990 just as well, and that doping was provided for FRG minors as well. West German politicians knew and sometimes even encouraged it. Striking detail: the study had been completed months prior, but the Department of the Interior only published a censored version after excerpts had leaked to the press. In the report the department disclosed, names of politicians were removed, because some of them were believed to be still in office at the time.

The study showed that the West German government spent an estimated ten million DM on 516 scientific studies into the performance-enhancing qualities of anabolic steroids, testosterone, and EPO. Coaches pressured athletes to take the drugs: whoever refused was denied important competitions. The side effects these studies showed were never mentioned. In turn, coaches and sports doctors were pressured by politicians with overly-ambitious objectives. People gladly looked the other way at official doping controls.

DOPING COMPETITION

So East and West Germany were involved in an actual doping race. Even if the structural doping abuse in West Germany wasn’t a direct answer to the GDR doping policy according to the Humboldt Universität study, the developments moved along evenly in both states. The report shows West German politicians wanted West German athletes to have the same opportunities as their East German colleagues. FRG had to perform as well as GDR, if not better. And to reach that objective, as far as politicians were concerned, anything was fair game. The 1972 Summer Olympics in Munich had started this cutthroat competition, when the GDR – in the lion’s den – won more medals than the FRG.

Those who expected the reunion of East and West Germany – both good for plenty Olympic medals – would result in a supreme sports country, were all disappointed.

Recently, the world’s strongest man died. His fate is considered symbolic for the athletic performances of East and West Germany. Gerd Bonk, a former GDR weightlifter, died aged 63. He’d used anabolic steroids for years, and won world title after world title. When in 1984 his performance decreased, he turned out to be worn-out. Bonk had diabetes, trouble with his kidneys and other organs, and ended up in a wheelchair. For another thirty years, Bonk lived ill and disabled, until he died from his defects in October of 2014. Once celebrated, but rather forgotten in reunited Germany.