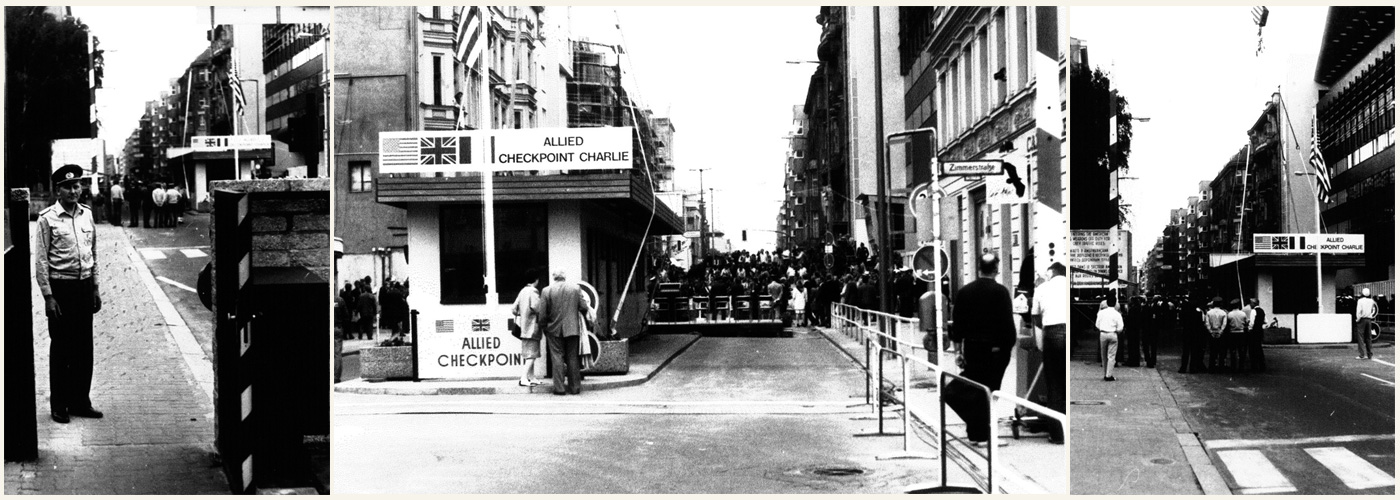

Every year, a group of seventy- and eighty-year-olds gathers to eat pizza in a Berlin suburb. For most of them, this is the only public occasion where they can freely talk about their past. They used to be colleagues. They are former passport control officers at the most famous border crossing of the Berlin Wall: Grenzübergangsstelle Friedrichstraße-Zimmerstraße, better known by its Western name, Checkpoint Charlie.

One of them is Peter (76), a tall, wiry looking man with remarkably large hands. Countless passports have gone through those hands. Peter was the head of the East German passport division for fourteen years. Fourteen years at the front line of the regime’s war against Republikflucht. In the first years after the Wall was built in 1961, many East Germans fled to the West, using a passport from a Western lookalike. In response, from 1964 onwards, passport control became the responsibility of the Stasi. The infamous secret service started to train the border guards to detect identity and passport fraud. In 1975, the year Peter started working at the Checkpoint, it had become almost impossible to flee with a false passport. Almost - but not quite; some people still managed to slip through the cracks. This was something Peter wanted to take care of.

Peter wants to remain anonymous, he doesn´t want his last name to be known. “If I would talk openly about the past, my neighbours and colleagues would turn against me. Everyone who at one time fought for GDR ideas, nowadays faces discrimination.”

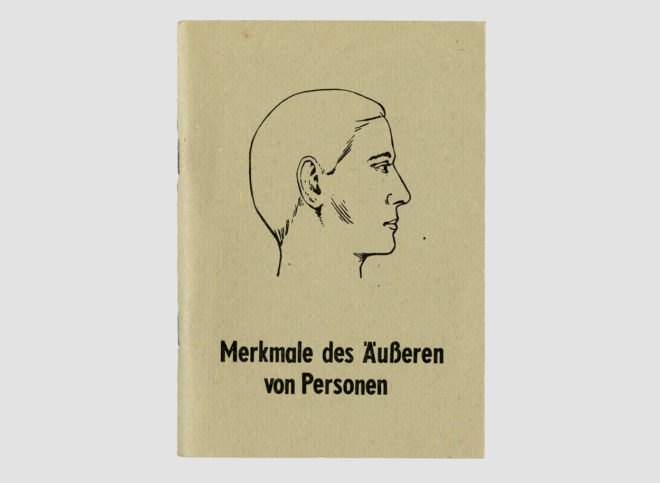

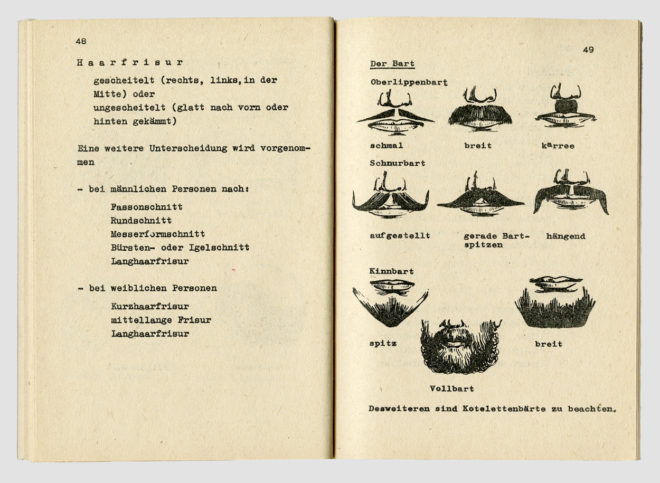

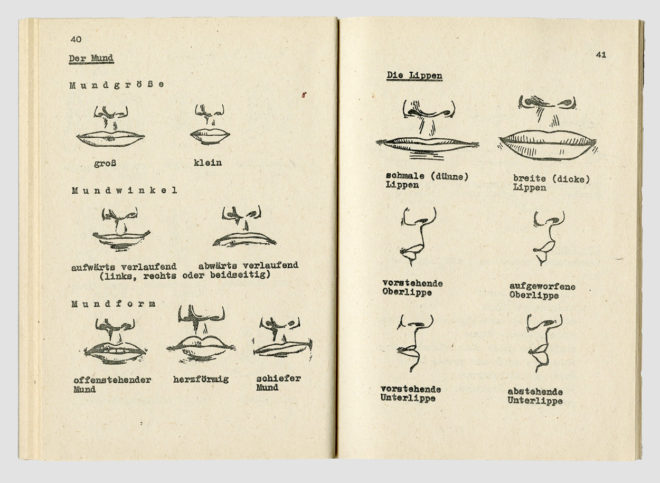

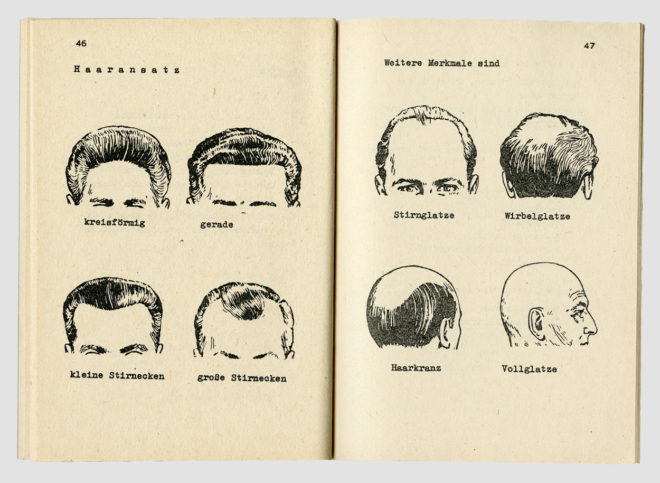

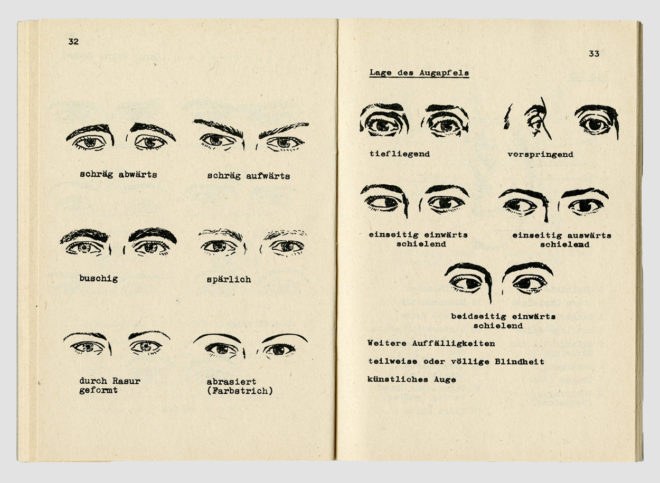

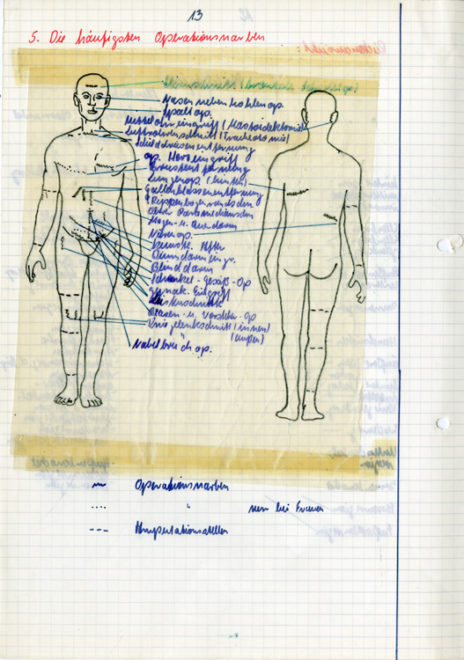

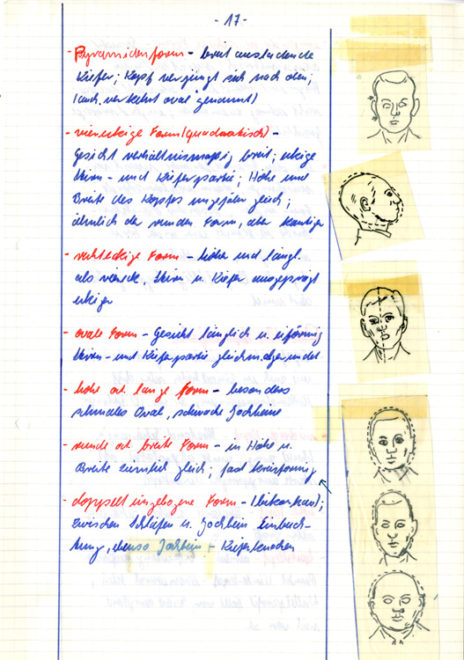

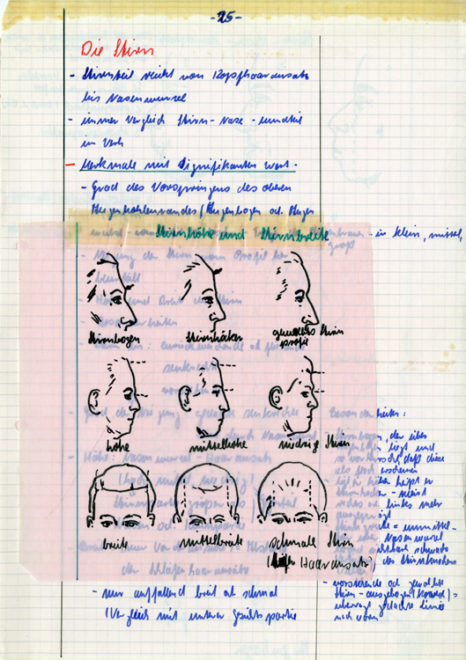

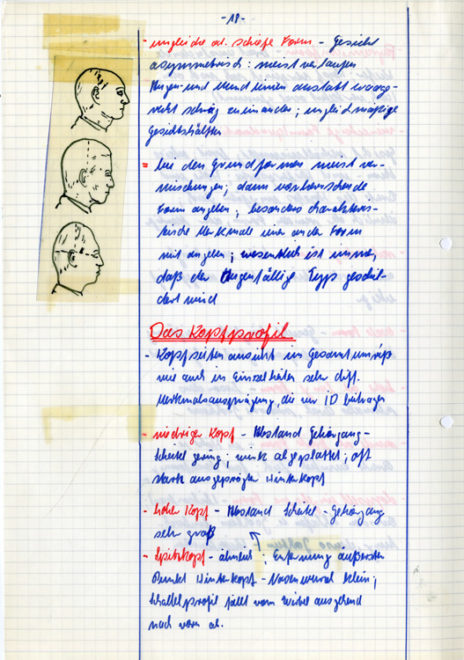

In his cramped apartment in a Berlin suburb, he keeps piles of Checkpoint Charlie material, including Stasi instruction booklets, full of pictures of different ears, noses, mouths and hairlines: facial recognition training material. Biometric technology avant la lettre.

Elke (46) from Dresden works for one of the leading facial recognition software companies. Just like Peter’s, the name of the company remains unmentioned. Being associated with the Stasi in any way will surely damage the company´s reputation. Germany has not forgotten how intensely the GDR population was spied upon by the secret service, and anything that reeks of surveillance still provokes a knee-jerk aversion. Which is something Elke´s employer wants to avoid at all costs. Elke emphasizes that what she shares are her personal opinions, not those of the company.

Elke grew up in Dresden, in the former GDR. “I had a really good life there, as a child”, she says. “It was a safe society, we had no financial problems and there was little competition.” But there was just one thing: she wanted to travel. “I have entrances in my diary from when I was twelve, thirteen years old, about how I was going to make it out of there, so I could travel the world. I wanted to go everywhere. To Paris, to New York, to go see the pyramids… But that was impossible, because of that stupid border. It didn´t make any sense to me, none.”

Peter is not unfamiliar with Fernweh, or wanderlust, either. One of the walls in his flat is covered with snapshots of vast mountain landscapes, with Peter standing in the foreground. When asked about the pictures, his eyes start to twinkle. He has been a mountaineer for all his life. With plenty of mountains in the Eastern Bloc countries, the Iron Curtain was not an obstacle for Peter. For him, the ‘anti-fascist protective wall’ (which is how GDR propaganda framed the Berlin Wall) was his everyday work environment, where he worked long shifts. On most days he worked for ten hours in a row, sometimes longer.

It was the toughest job he ever did, he says. “Not only did we have to check passports for possible fraud. We were also responsible for maintaining order. And we hardly ever succeeded in doing that. Not a day went by without a disturbance: from Western protests to drunk East Germans who demanded passage to the West.”

Meanwhile, people still managed to pass through the security checks with borrowed or stolen identity cards. Not just from East to West, but in the opposite direction as well. Many Westerners regularly went shopping in East Berlin, or had a sweetheart there. People who overstayed their travel visas for East Berlin faced travel restrictions: they couldn´t cross the border with their own IDs any longer. So they used other people´s papers. “We usually discovered the fraud only after someone else had already crossed the border with it, when someone reported the passport stolen.”

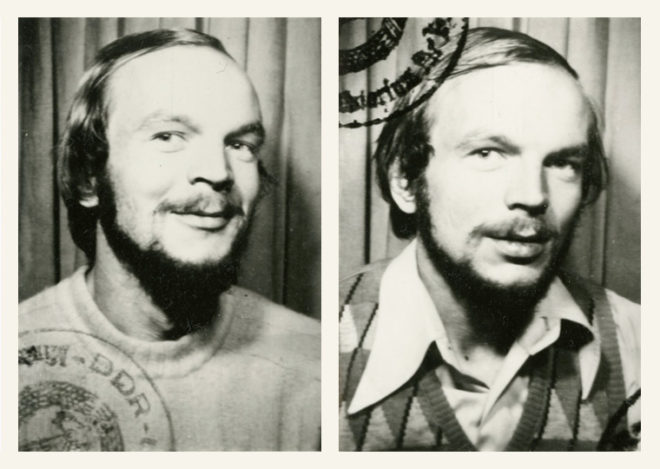

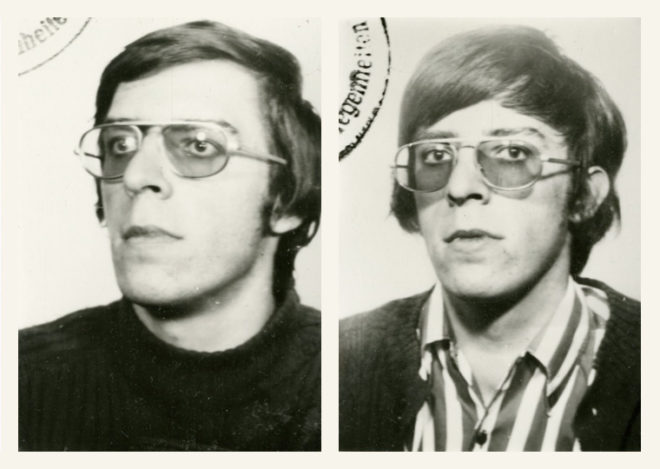

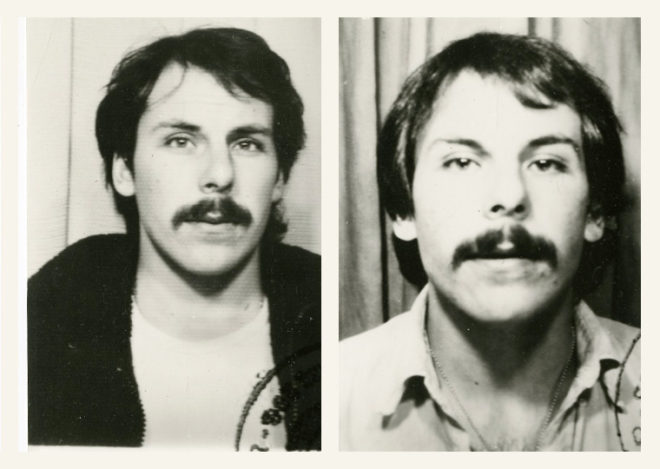

If there´s one thing Peter can´t stand, it´s a job done badly. He had specialised in facial recognition at a Stasi college in Potsdam. Now he wanted to use this knowledge to improve the facial recognition training at the border, by making it ´more scientific’. So in 1977 he started his research. He investigated what parts of the face his experienced colleagues would focus on, and trained newcomers to do the same. He also taught them to mentally break down faces in component parts, so as to learn to look at the details. He also started to secretly take pictures of travellers and their passport photos. “That was difficult. Only one in twenty pictures came out right.” With resulting sets of pictures – some matching, some not - his colleagues practised their skills.

Although he is a convinced socialist, Peter claims that ideology was not what motivated him to improve the border procedures. On the contrary, ideology could cloud one´s vision. Objectivity was what Peter was after. “I just wanted the work at the border to be done well.” But at a border as controversial as the Iron Curtain, there simply is no escaping politics or ideology. During the eighties, while Peter steadily worked on his method, discontent started rumbling in the GDR.

Towards the end of the summer of 1989, people in Leipzig started to openly protest against the government. Soon, the demonstrations spread to Dresden. For Elke, then 19, the political unrest coincided with a deep personal crisis. “Everything was adrift, the country as much as I was. For months I had had no idea what to do with my life. All the girls became teachers – there was not much else to do. But I did not want to be a teacher in that country. Becoming a teacher meant having to adhere to all the nonsense they were teaching the kids. That communism is the best system, that we were going to take over the world. We were already laughing about all this - openly making fun of the teachers, who, frankly, had run out of arguments. So, no educational career for me. But then what? Desperate and clueless, I decided to take an apprenticeship as a hairdresser. At least that was politically neutral. ”

When the Iron Curtain started to crumble in Czechoslovakia and Hungary, and more and more of her friends left, Elke stayed in the GDR to finish her training. She just could not handle more uncertainty.

But she also could not stay away from the protests. “I felt intuitively that something important was going to happen. It was so impressive: the huge crowds, moving through the city, like a giant beast that just kept growing. All those different people of all ages that came together.”

It wasn’t anger that drove her to the streets, she says: “The ideological nonsense at school, the opened mail and tapped phone calls. That was just there. It was not something I would go in the streets for. But the years and years of longing to travel, that is what I carried with me during those demonstrations.”

On 7 October 1989, the GDR celebrated its 40th anniversary as if everything was fine. On the same day, Peter presented his work in the form of a learning cabinet to his colleagues. It was meant to become the foundation for a training for all passport control officers.

Meanwhile, the protests intensified. From tens of thousands the masses swelled to hundreds of thousands. Demonstrations spread to other cities, including Berlin. The regime started to falter.

On the evening of 9 November, Peter is at home, watching GDR politician Günter Schabowski announce on television that the border will be opened. When a journalist asks him when this measure is supposed to take effect, Schabowski makes a historic mistake. “Immediately,” he answers. What he should have said was: tomorrow - the border guards had not yet been informed. Peter puts on his uniform and rushes to Checkpoint Charlie, where a huge crowd has gathered, demanding immediate passage. Within hours, the guards give in. The rest of the night, Peter is busy managing the flow of people going to the West. “It was then that I realised that life would never be the same. But nobody knew what would come next.”

For Peter, the fall of the Wall marked the beginning of an uncertain transitional period. For months, he still went to work at the border, every day. He even continued to train new border guards, using his own method.

Elke did not travel to the West right away, as so many former GDR citizens did. Only weeks later, on a freezing December morning in 1989, she crossed the border in Berlin for the first time. “I can’t remember whether they still checked our identity cards, or just let us pass. We had left before daybreak to avoid the crowds. That had worked. But then we stood there, at six o’clock in the morning, in West Berlin. Not a single café was open yet and it was horribly cold. The only warm place we could think of was Tegel, the airport. So that is where we went. I will never forget sitting there, watching the hordes of business travellers passing by. All those people, travelling around the globe, like it was the most natural thing in the world. To New York! Madrid! London! That must be so cool!, I thought. That was what I wanted to do too.”

On the 22nd of June 1990, seven months after the fall of the Wall, Checkpoint Charlie was dismantled. The demolition work was done by the former border guards, people who had worked there for decades. Peter was there too. “It was quite emotional, of course. All of a sudden, the work that you have done half a lifetime isn’t necessary any more. Yet I also felt a heavy burden being lifted off my shoulders.” Guarding a border that almost nobody had wanted had been very, very hard work.

He tried to interest the new German border control officers in his facial recognition method, but to no avail. In the new Germany, ‘Stasi technology’ was not met with much enthusiasm. “And they were already Komputer-Infiziert, they expected computers to take over soon.” In August 1990, when he was officially discharged as a border guard, he took all his notes and study material home.

gallery

Twenty-six years later, computerised facial recognition methods are increasingly being used to support border control procedures. Mostly for passport controls, but sometimes for monitoring migration as well. Proponents of the new methods see it as a promising new weapon in the fight against identity fraud and terrorism. But scepticism about the technologies is growing. If an image of your face is linked to your personal information, how safe is that information? What if the technology falls into the wrong hands? Doesn´t it have a totalitarian potential?

Elke´s employer carefully scrutinizes all its customers, she emphasizes, to see if they meet certain ethical standards. With some countries the company refuses to do business at all. Which ones? “The usual suspects, mainly countries in the Middle East.”

The company also sells facial recognition software for border control. For EU borders, among others, which are becoming increasingly impenetrable for those who do not have the right papers. Isn´t this a strange job for someone who helped tear down the Wall? Doesn´t the fortification of European borders remind her of the GDR?

“No, this is different,” she argues. “The Wall effectively imprisoned people in their own country. That is different from measures to protect borders. That is what current border technologies do: protect against terrorism and illegal behaviour. Of course I know that immigrants feel locked out. But the alternative, mass immigration, would disrupt societies. As long as there are national borders, border control is necessary. Think also of the huge threat of terrorists, who are able to cross borders and organize themselves. I’m in favour of more stringent border controls to prevent attacks.”

Peter is more willing to compare the Wall with present-day borders. He doesn´t think his work at Checkpoint Charlie was very different from the work countless other border guards do, all around the world. He refuses to think of his work as something other than just a practical job: the border was there, and someone had to guard it. “I could have done the exact same work in the Netherlands.”

So Peter is not ashamed of his past, and neither are his former colleagues. On the contrary, they are proud. Not of the historical impact of their work, which Peter considers minimal. He even doubts whether his facial recognition training made any difference. No, the veterans of Checkpoint Charlie are proud because they successfully carried out a very difficult task. In their opinion, reunited Germany has treated former Stasi employees unfairly, by ‘demonizing’ them. But what can you do, says Peter. “History is written by the victors, and we are the losers.”