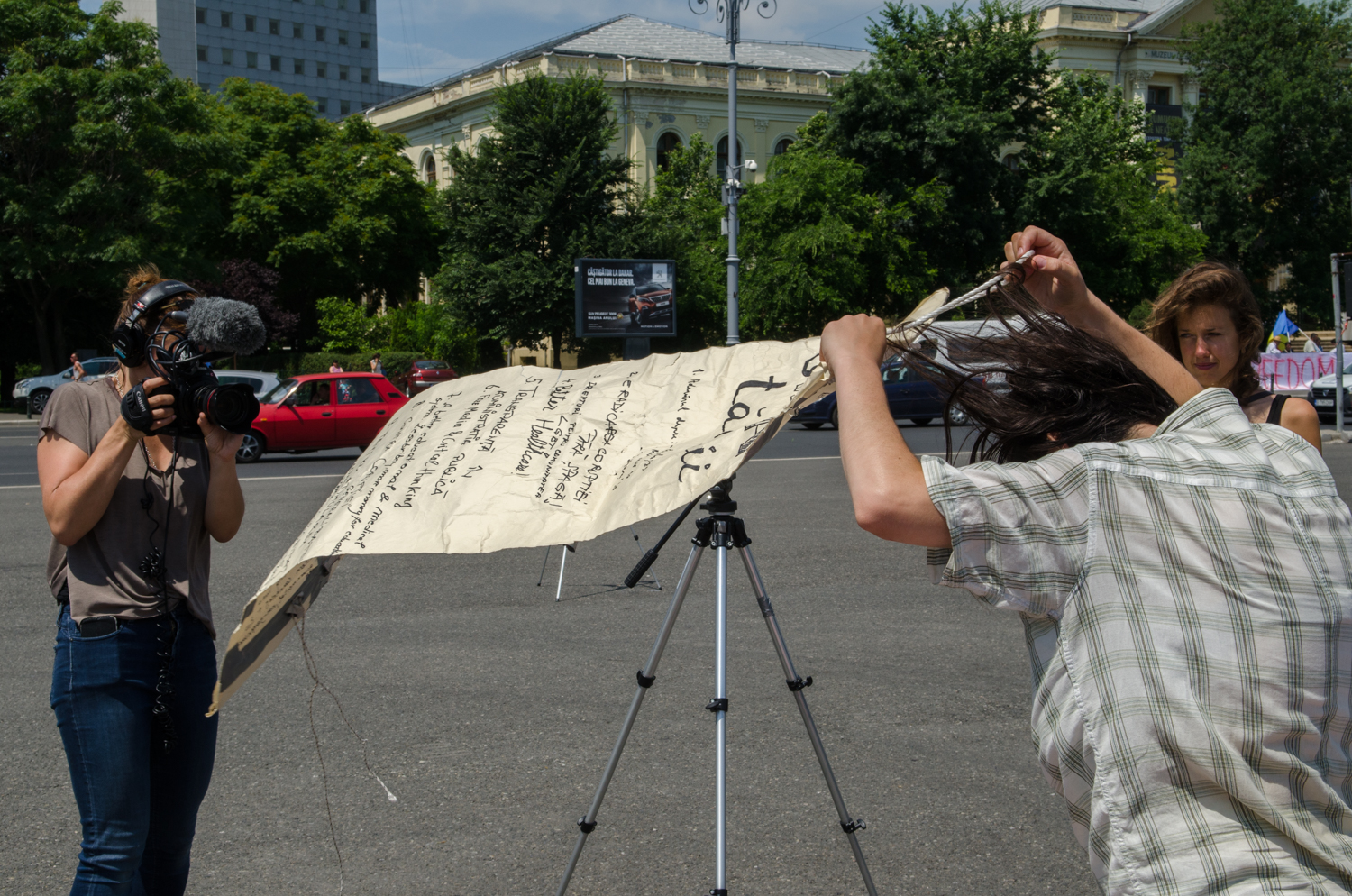

Bucharest – Ioana Tudor practically risks her life making her way through the onslaught of traffic to get to Victoriei Square in front of the Romanian government building. The inhospitable plain of asphalt can hardly be called a square. It is encircled by a four lane road where the traffic of eight broad boulevards meets. It is hard to imagine that only a few months ago, the place was packed with anti-government protesters as far as the eye could see. Now, the square is empty, except for Tudor and two colourful banners: one reads ‘#resist’, the other one ’#insist’. It is a modest reminder to the men and women in power: we are still here.

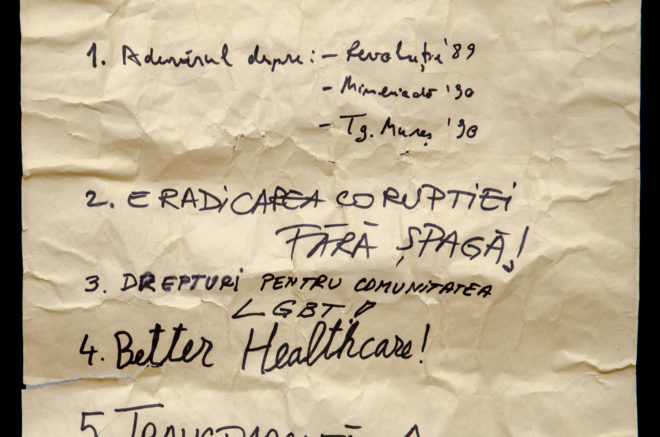

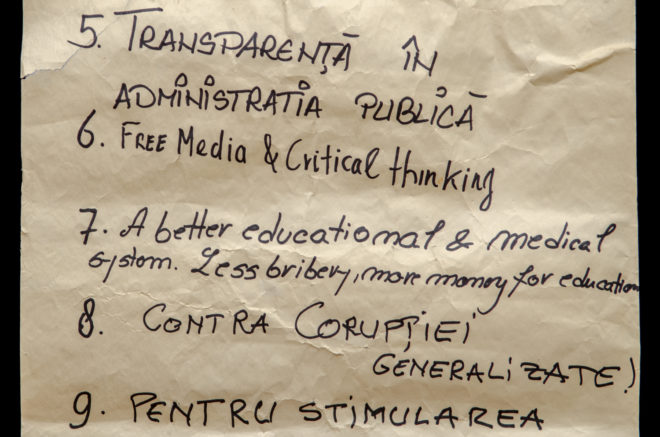

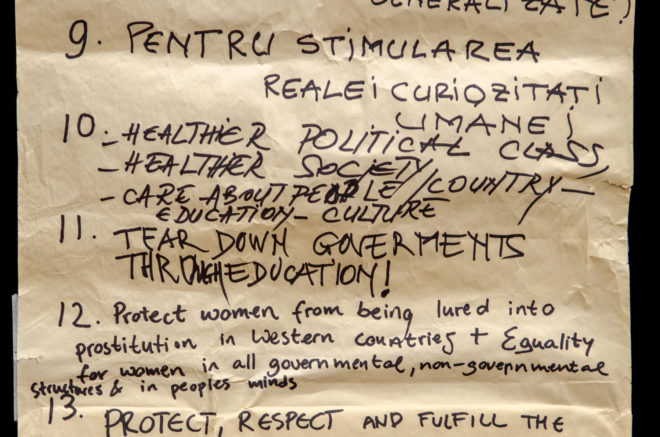

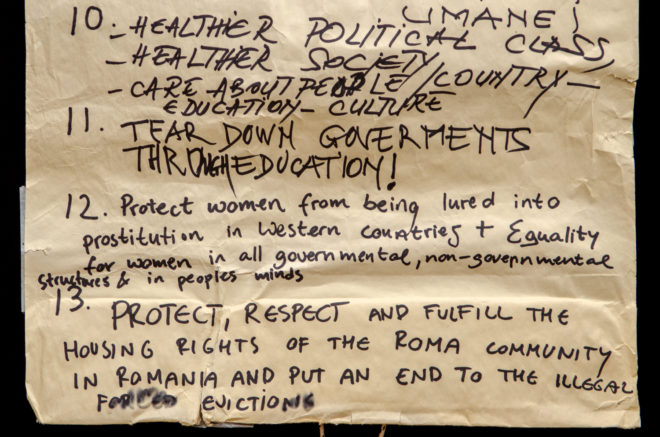

Tudor chooses a spot right in front of the government building. She rolls out a small carpet in the shape of a target and takes place on the bullseye. Around her neck, she wears a piece of paper that reaches to her ankles. ‘Greva Tacerii’ it says with bold black letters. In other words: ‘Silent strike’. Below, thirteen demands from the government are scribbled by different hands. It is eleven in the morning. From this moment, she will be silent for five days, just like her father 27 years ago. His silent strike against the Romanian government changed his life and his daughter’s life.

foto groot

Art performance, protest and tribute to her father

Ioana Tudor (36) was born in Romania but found herself as a 9-year-old girl with her father, mother, brother and sister in an asylum seekers centre in the Netherlands. She grew up in that small country and became a theatre and performance artist. Her work is always socially engaged, and her past frequently plays a part in the background. In her art performances, she often asks a lot of herself, and this time is no different: she will not utter a word for five days. On top of that, she will stand still in one spot for eight hours every day.

She gathered the demands on the piece of paper around her neck from interested citizens of Bucharest in the days up to the performance: an end to corruption, better health care, equal rights for LGBT-people, free press, and justice for the victims of the Revolution were some of the things the citizens wrote. ‘Silence is a useful instrument for protest,’ Tudor says. ‘Governments prefer to gag critical thinkers. It gives you the opportunity to make “noise” by remaining still.’ Tudor’s silent strike is not just an art performance but also a protest and a tribute to her father.

The enemy of democracy

The strike of silence of Dumitru Tudor started in 1990 by accident, he explains in his home in Enschede a few weeks before his daughter’s departure for Romania. It happened during the violent period that started after the Romanian Revolution in 1989. After the execution of Nicolae Ceaușescu, Ion Iliescu, a former communist, came to power. The new leader imposed restraints on the fledgeling free press and came down violently on the protests against his government.

Tudor came to the centre of Bucharest to size up the protest. ‘I raised my fist at a police helicopter in a burst of anger.’ Those images were shown on the news, and he was considered the leading man of the protest movement. He was labelled ‘the enemy of democracy’.

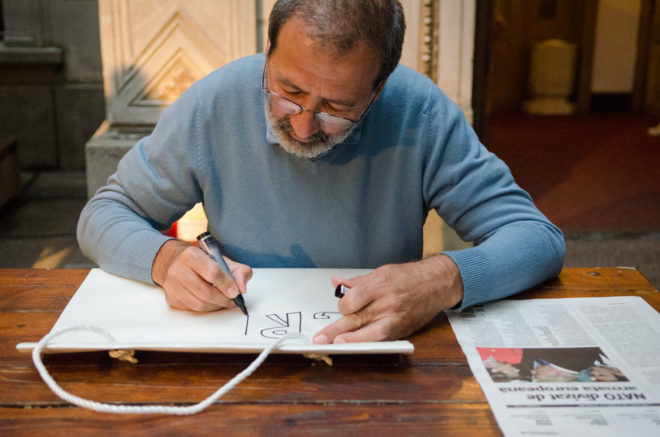

Tudor: ‘I knew everything was over and that I would no longer be free.’ At home, he grabbed a piece of paper, wrote down ‘silent strike’ and below it his thirteen demands from the government. Sitting at the kitchen table, he shows his daughter what he did. Greva Tacerii he writes with a pencil, the last two letters almost falling off the paper. Ioana smiles: ‘It’s so funny, this is exactly what happened then too, I recognise it from the pictures. I always do that as well!’ Her father thinks it is genetic: ‘The silly thing about us is that we don’t really think about the consequences.’

Vader en dochter (video)

In her father’s home in Enschede, Ioana discusses his silent strike from 1990 in preparation for her performance.

Dumitru Tudor’s thirteen demands from the government were not that different from the requests the citizens of Bucharest make now. They want a free press, for example, and that the people responsible for the violence against the protesters in 1990 are brought to justice, something that still has not happened 27 years after the fact, much to the frustration of many Romanians. ‘And then I just started standing there. Like a fool.’

‘The silly thing about us is that we don’t really think about the consequences.’

He stood there for four days, in front of the Hotel Intercontinental in Bucharest, the preferred accommodation of the Western press. He was arrested when pictures of him started to appear in the newspapers. After four months, he was released from prison, and he fled to the Netherlands with his wife, the then 9-year-old Ioana and his two other children.

Watch this short documentary about the impact of the flight on Ioana Tudor and her father

Tudor senior has mixed feelings about his daughter’s performance: he is proud of her, but at the same time he thinks that his daughter’s generation should come up with a more effective way of protesting – something with more impact. He is disappointed about the lack of change in his country in almost three decades after the revolution. Many of his fellow countrymen feel the same way. At the height of the protests this winter, over 500,000 people took to the streets. ‘We stand here as our parents did in 1989’ some protest signs read.

foto groot

‘Thieves, thieves!’

Corruption has been a large problem in Romania for decades. Every resident knows that paying bribes, in the form of a bottle of expensive perfume if necessary, is sometimes the only way to get things done. Last January, the government announced by decree that corruption offences under 44,000 Euros would no longer be punished, a measure especially favourable to civil servants and politicians.

The public outrage that followed the order led to the largest demonstration since the Romanian Revolution. It continued for weeks; people defied freezing temperatures and locked up their business just so they could join the protest. Deep into the governmental palace, their yelling must have been heard: ‘Thieves, thieves!’

PR consultant and friend of the Tudor family, Simona Istrat, was present. She was 16 when Ceaușescu was executed. ‘My generation is a lost generation. After the fall of communism, we were mainly focused on earning money, building a house, a life. We stayed away from politics, something I regret now. In January it was the first time in my life that I joined a protest. I want a better country for my 16-year-old son.’

‘I believe that one person can be a catalyst.’

After seventeen days of demonstrations, the government repealed the corruption decree, but hardly anything else changed. Most protesters went back to their own lives, but a small group of fanatics persevere. Every night at nine o’clock, a few dozen people come together in the square. The day that Ioana Tudor begins her performance, they have met there for 132 days in a row. They sing the national anthem and chant slogans in the direction of the government building, which does not give way.

Ioana Tudor performs her silent strike for her former fellow nationals: ‘I share a past with them. I do it out of solidarity with the people who feel that fire that urges you to make a change. I believe that one person can be a spark, a catalyst, but the revolution also needs solidarity.’

‘Millions of people should be standing here’

At the end of the first morning, it starts to rain. Armed with a red umbrella, Tudor is standing with her back to the government palace. The massive building seems to be hiding behind a group of tall trees. The windows in the strict façade only reflect dark clouds, not a civil servant or politician in sight. Her father comes walking across the square. He embraces her and is trying hard to hide his tears. ‘Millions of people should be standing here, but she is all alone,’ he mumbles, shaking his head when he leaves.

On the second day, the rain makes way for abundant sunshine. It is very warm; the asphalt gives off a sweltering heat, the air is saturated with exhaust gasses. People in buses look half-interested at the woman with the sign around her neck, standing in the square. Now and then, someone crosses the street and reads the paper on Tudor’s chest while nodding approvingly. On day three, things become tough, and reinforcements in the form of compression stockings are called in. One of the first demonstrators decides to join Tudor in her silent protest. Calin Andrei draws a triangle with chalk next to Tudor’s target. He puts a piece of tape with a cross on his mouth. Day four, another protester joins in, and now Tudor is flanked by two men.

Timelaps (video)

‘I could hold his hand in retrospect’

Remaining silent came easier to Tudor than standing still in the same spot for hours on end. ‘It enabled me to really look at people. Words can get in the way, are often cliches. I could not hide behind them anymore.’ She thinks her performance has strengthened some of the protesters and has also helped her father. ‘I could hold his hand in retrospect. Maybe he was able to process a bit of his past through me. I saw the pride in his eyes. The performance contains elements of joy, humour and positivity and I think he saw that, which also makes his own past less dark in a way.’

After five days of keeping silent, ‘hoi’ (which means ‘hi’ in Dutch) is the first word she utters. ‘I’ll think of something better next time,’ she says. It feels strange to leave the square after five days, as though she is abandoning her former fellow countrymen. The next day, of all days, the Romanian government falls, succumbing to an internal power struggle. Calin Andrei removes the banner that reads #resist from Victoriei Square. He leaves the other banner, the one that says #insist. A week later, Simona Instrata, friend of the Tudor family lets them know that ‘nothing has changed. Everyone is just waiting quietly to see what happens next.’

This story also appeared (in Dutch) in a shortened form in the magazine Wordt Vervolgd.

foto groot